Introduction

Cutaneous dysesthesia is one or more abnormal sensations that occur in the absence of primary cutaneous findings or stimuli and often includes sensations such as pruritus, tingling, burning, allodynia, hyperesthesia, or anesthesia.1 The main etiologies of cutaneous dysesthesia are divided into central, peripheral, or idiopathic. While cutaneous dysesthesia is often associated with various disease processes affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems, up to 40% of patients are thought to have idiopathic disease.

Cotterill first described psychogenic cutaneous dysesthesia, now referred to as idiopathic cutaneous dysesthesia (ICD), in 1981 as “dermatologic non-disease” characterized by generalized skin pain without associated rash.2 Early work by Koblenzer found that patients with ICD commonly present in the 4th to 6th decade of life and have associated psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety, depression, and somatization.3

Dermatologists are often confronted with how to treat the patient with ICD, a condition often challenging to formally diagnose and treat. While there is little primary research on this condition, this narrative review aims to summarize what is understood of the pathophysiology of the condition and how to diagnose ICD. Additionally, common psychiatric comorbidities and recommended management are reviewed. Due to the interplay of psychiatric comorbidities and ICD, we emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary management including both psychiatric and pharmacologic approaches to this condition.

Pathophysiology

Cutaneous sensation is a fundamental aspect of the human experience and is integral in human connection, pleasure, and protection. Three nerve fiber types mediate cutaneous sensation, A-beta fibers (myelinated mechanoreceptors), A-delta fibers (myelinated free nerve endings responsible for nociception and thermoreception), and C-fibers (small, unmyelinated nociceptors).4 These fibers detect stimuli and transmit signals to the central nervous system (CNS) by the synaptic release of neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine). Within the brain, these signals are interpreted into sensations such as temperature, pressure, and pain. If acute or chronic injury occurs to nerve fibers along this pathway, derangements in communication between the peripheral and central nervous systems may occur via false detection or amplification of signaling. While little is understood on what causes the derangements on the biochemical level, it is known that the deranged communication manifests as cutaneous dysesthesias.

Diagnosis

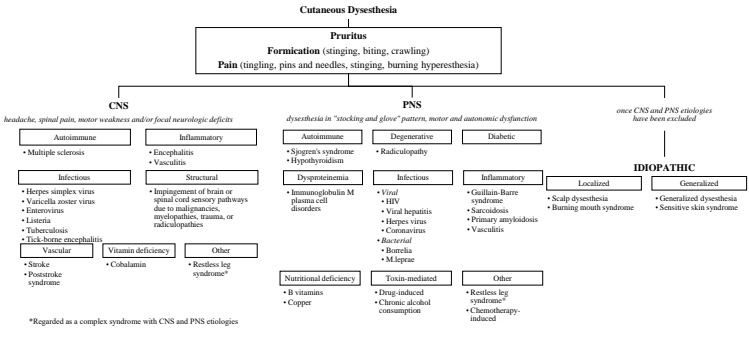

ICD is a diagnosis of exclusion after potential central and peripheral etiologies have been effectively ruled out (Figure 1). Dysesthesia may be a presenting symptom of a primary medical disorder or infection, and thus a thorough history, physical exam, and supplementary laboratory and imaging studies should be obtained. Referral to other specialists such as neurology, rheumatology, and infectious disease may be warranted based on initial work up. CNS-related pathologies that cause generalized dysesthesia may be summarized into the following etiologies: inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, vascular, structural, and vitamin deficiency (Fig. 1). In addition to dysesthesia, these conditions often present with headache, spinal pain, motor weakness, and/or focal neurologic deficits. Alternatively, peripheral nervous system (PNS)-related pathologies that cause cutaneous dysesthesia may be summarized into the following etiologies: degenerative, diabetic, infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, dysproteinemias, toxin-mediated, nutritional deficiency, and other (Fig. 1). These often present with neuropathies in a “stocking and glove” pattern with dysesthesia occurring first distally in the hands and feet, in addition to motor and autonomic dysfunction.

Psychiatric Comorbidities

ICD may be associated with psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, somatization, and personality disorders.5 This is supported by a case series of 11 female patients with scalp dysesthesia, many (5/11) of who were previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and reported symptom exacerbation with stress. Of the 11 patients, 9 reported improvements of symptoms with low doses of antidepressants. Unfortunately, this is the only study to date that provides quantitative analysis on the association of psychiatric disease and ICD. Regardless, it is important for the dermatologist to address associated psychiatric disease.

Management

Currently, there remains a paucity of formal guidelines for the management of ICD. Patients are often frustrated by the idiopathic nature of their dysesthesia, the generalized lack of knowledge of the condition and the lack of standard treatment. Explaining the diagnosis and management of ICD is oftentimes daunting. Because of the frustration around the lack of knowledge on this condition, we recommend focusing on what is known of ICD and validating the patient’s experiences with ICD. Setting initial expectations of patient’s disease and likelihood of cure significantly alters their perception of treatment success and overall satisfaction, so we suggest the following to approach the conversation with a patient with ICD6:

“We do not know what is causing the dysesthesia, but that does not mean it is not a real medical condition. We know that something is causing the nerves in the skin to fire abnormally that causes the dysesthesia. We know that mental health can be strongly impacted by this condition. Currently, treatments include medications to calm down the nerves, as well as medications used to help you cope with the psychological toll that the condition can have. While it is extremely difficult to cure dysesthesia, it is possible to find relief, and oftentimes it requires trialing several modalities over the course of months to find the most optimal treatment regimen.”

Furthermore, because ICD is commonly associated with psychiatric comorbidities, it is essential to have a multidisciplinary team that includes dermatologists and mental health providers to be involved in managing patients with this condition. We recommend both psychiatric and pharmacologic management as outlined below for best patient outcomes.

Psychiatric Referral

The clinician must be extremely prudent when proposing a psychiatric referral, emphasizing to the patient that ICD is a real dermatologic condition despite having no primary cutaneous findings. We recommend the dermatologist start the conversation that patients with ICD have often encountered difficult life events prior to their symptoms starting. The dermatologist can then inquire about any prior life stressors or known psychiatric history. We recommend reassurance that the reason for psychiatric referral is because, despite lack of knowledge of the exact etiology of the disease, it is known that ICD results in significant impairment of quality of life and mental health. It is important for the dermatologist to approach these patients with empathy and recognize that psychiatric comorbidities are often aggravated by lack of an established etiology and definitive treatment options in ICD. Furthermore, as mentioned above, psychiatric illness may precede the onset of ICD, and there may be common pathophysiologic mechanisms between psychiatric disease and ICD.

There are multiple modalities available to offer psychologic support. Some viable therapeutic modalities that may replace maladaptive thought structures that exacerbate disease include cognitive behavioral therapy, psychiatric intervention, or marital/family therapy.7–9 Additionally, participation in mindfulness-based classes (eg, tai chi, yoga, and medication) and support groups can aid to normalize the diagnosis and provide additional support beyond that of the dermatologist.8 If a patient has Medicare Advantage or Medicare supplement insurance (Medigap) plans, it is worthwhile to inquire on interest in exercise, as they may have coverage for gym memberships, drop-in classes, and other fitness options.10 This holistic approach is likely to provide the most benefit to patients with ICD.

Pharmacologic Management

ICD can be a difficult condition to manage, and there is minimal literature regarding its treatment. Initial work by Koblenzer demonstrated near complete resolution of cutaneous dysesthesia characterized by burning and exquisite sensitivity to sunlight in a 54-year-old woman with concomitant major depressive disorder treated with pimozide 3 mg/day.4 Additionally, Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) alone or in combination with pimozide has been reported to result in complete resolution of symptoms of burning, stinging, shooting sensations, or “coldness” in 4 patients with ICD.5 Reported treatment of burning mouth syndrome, considered a localized form of ICD, includes a combination of topical and systemic therapies including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), capsaicin and gabapentin11 (Table 1). Topical agents used for pruritus and other forms of cutaneous dysesthesia, such as capsaicin, lidocaine, and compounded creams (eg, lidocaine/ketamine/gabapentin/amitriptyline) are commonly used by dermatologists for ICD.12 While it may be reasonable to consider initially treating with topical agents as they boast safer adverse reaction profiles, topicals are less likely to be efficacious in treating ICD than systemic therapies. This can be attributed to the ability of systemic agents to directly mediate affected nerve fibers associated with cutaneous sensation that are injured in ICD. Unfortunately, there is a lack of large-scale, prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized trials investigating the safety and efficacy of the above treatments for ICD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the diagnosis of ICD is one of exclusion once potential CNS and PNS etiologies have been ruled out. Treatment is difficult and requires clinicians to set realistic expectations and goals. Because ICD is often preceded by or associated with concomitant anxiety, depression, somatization, and personality disorders, the dermatologist should recognize the associated psychiatric burden and recommend psychiatric referral. Drugs that are highly efficacious for neuropathic pain, including gabapentin, pregabalin, TCAs, and SNRIs, are sometimes effective in treating ICD. It is crucial for the dermatologist to approach these patients holistically with empathy and foster a strong therapeutic alliance by recognizing ICD as a legitimate dermatologic condition despite lack of primary cutaneous findings.

Disclosures

Megan Hauptman, Jeffrey Sobieraj, John Koo, and Mio Nakamura have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. This article has no funding source.